|

New Housing Solutions for Cities in Change - 14th Alvar Aalto Symposium

Prof Markku Hedman © Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation Prof Markku Hedman © Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

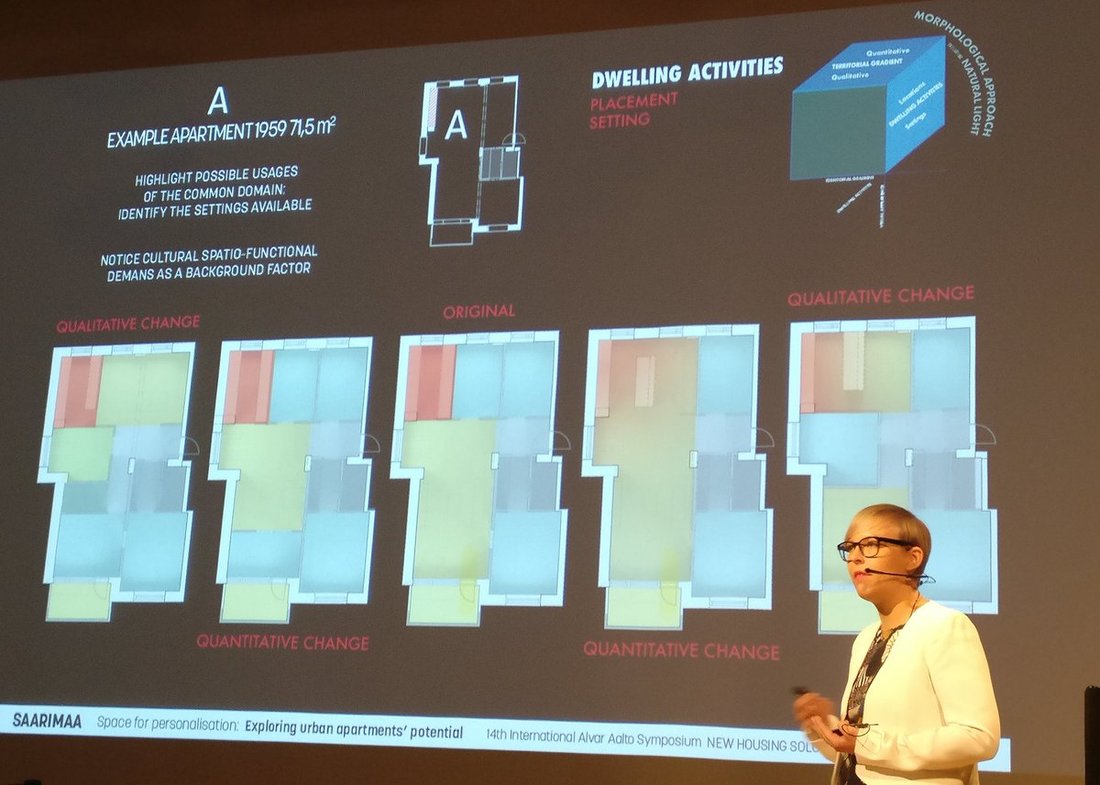

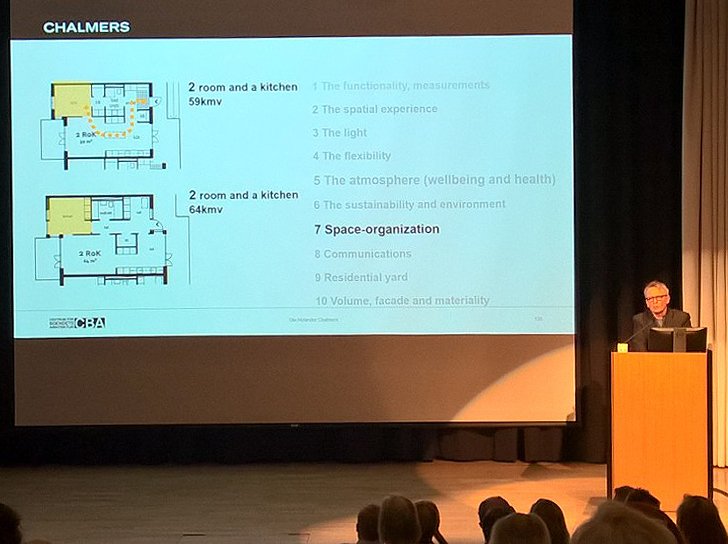

The 14th International Alvar Aalto Symposium aimed to open up discussion and sharing about ‘NEW HOUSING SOLUTIONS FOR CITIES IN CHANGE’. It is a three-yearly impressively well organised event, with different themes. The focus in 2018 was on the present challenges and possibilities for future urban housing design and construction. Four ambitious themes were constructed, such as ’cultural variables’, ‘sharing’, ‘adaptability’ and ‘emerging typologies’, though there were several talks in reality some talks covering wider themes and other building programmes. The symposium was chaired by Professor Markku Hedman, who is Director General at Building Information Group in Helsinki and MD of a-live architects in Helsinki (and prior to this Housing Design Professor at Tampere University Technology). Under the stewardship of Professor Hedman, the symposium included both young and established active architecture practitioners as well as researchers in the field of future urban housing. It was also one of the few events in the industry that I have attended where speakers and moderators were (almost!) entirely gender balanced. I was told that the mix of practice-active and research-active speakers and audience members was a first: there is after all a separate research conference every three years. Though for me the key to success was exactly this diversity in expertise and approaches, leading to some interesting ‘on-the-side’ discussions. Admittedly, the amazing side activities and organisation and the conference location (Aalto’s Jyvaskyla University) also add to the success of the symposium. It seems that there are still some architects in the Nordic region combining academia and architecture practice, which gives refreshing perspectives and keeps their academic research relevant to the real world. This combination of researcher-educator-practitioner is a ‘dying breed’, especially in the UK, due to the pressures of academia for research funding and outputs, and the increasing lack of value placed on artistic/practice work and the difficulty in combining practice and part-time academia. I am however informed that also in the Nordic region this researcher-educator-practitioner model is also less common than it used to be. (This ofcourse has repercussions for architectural education, given that there is a danger that a generation of architect-educators who may never have practiced, will be teaching future architects on… how to practice! But that discussion is for another time). This is why I really valued the mix of architecture research and practitioners from the Nordic region, who were the target audience, and other European countries coming together, as it is a timely reminder about the challenges that architects face in housing design (and generally in practice). It also became apparent that there are country-specific challenges that are not in common throughout the EU. For example Professor Jeremy Till talked about the ghastliness of the pressure towards ‘micro-flats’ in the UK and how some developers market developments based on not having affordable housing and a mix of people living there (and in some cases these ‘micro-flats’ are 13 to 15 m2 ‘rooms’). He rightly reminded the audience that without a discussion about tenure, finance and land ownership and politics, it is limited what we can achieve in terms of quality. Dr Jyrki Tarpio from TUT also referred to this in his research, based on ‘Dwellers in Agile Cities’, examining existing solutions and looking what works in terms of inclusivity and agility to the create new solutions. Architect and researcher Sini Saarimaa from TUT looked at lessons to be learned when apartments when considered from the point of view of personalization. Professor Ola Nylander, director of Centre of Housing Architecture at Chalmers University, presented research related to flexibility and adaptability, both highlighting the value of research in housing design and how this knowledge can underpin the architects’ ‘evidence based design’ in their dialogue with the client and developer. Professor Nylander evidenced the value of an additional 5m2 on a well-designed apartment layout, bringing enhanced qualities and adaptability over time. He also presented possible ways to quantify the quality of housing design with 10 or so categories; and while it was unclear how the categories were decided on and what their weighting might be, this research could give architects more agency by access to this knowledge while designing and arguing for good quality in housing design. Or at least that is the intention of this research. The themes of flexibility – approached from different perspectives – was key to several speaker’s approaches to the symposium’s title: “new housing solutions for cities in change”. |

But, it appeared that some of these presentations were also some of the more controversial talks perceived by some of the delegates and other speakers. It became clear that the role of the architect and the discussion about quality housing design takes on different dimensions throughout Europe. For example the challenges faced in the Nordic region (such as the diminishing role of the architect, diminishing fees, and pressure for downward quality in architecture) are not those faced in other regions (such as Germany or Switzerland), where architect’s fees appear significantly higher, and architects appear to have more agency still in housing design quality decision-making; i.e. their voice is still heard by the client and developer. It is reassuring to hear that in some regions, there appears less of a pressure for less space, less quality and this downward spiral for smaller and smaller ‘cells’ as homes. But unfortunately this is not the same reality everywhere.

As a result, some of the research that attempts to ‘quantify’ housing design qualities might appear ‘excessive’ to those not facing the same financial and quality pressures. In fact some delegates posited that attempting to quantify good housing design qualities, might take agency away from the architect: why need an architect at all, when the mapping of good quality housing design can be treated as ‘patterns’ to be copied? Contextualising our research and practiceAs I understand it, the research mapping of good quality housing design is to support architects in practice to ‘design with knowledge’ - i.e. making the invisible and intuitive more visible and highlighting the ‘hidden’ value of this through exemplary case studies, not patterns to be copied. Copying would miss the point as the qualities are contextualised for each project and site, and indeed are region specific (e.g. it is based on existing building standards and responds to local typical space standards, climate and expectations). The contextual nature of what we understand by ‘housing design quality’ was also illustrated by some of the interesting and beautiful urban housing plans and designs shared of non-Nordic projects (such as by Anne Kaestle at Duplex Architects, by architect and Chair for Design and Housing at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Verena Von Beckerath at Heide & Von Beckerath Architects; and by architect and Associate Professor Elli Mosayebi at ETH Zurich and at Edelaar Mosayebi Inderbitzin Architekten). From discussions however, it became apparent that such projects would generally not be possible in the UK or in much of the Nordic region due to different financing models and expectations/realities about land-use and tenure. Equally I suspect non-Nordic delegates might have been puzzled by some of the other regions’ exemplary housing design, as the issues they face are so different. Obviously all of this is highly contextual and must be framed within the different boundaries that architects operate within, in different regions. I do think each of us speakers could (and should have) been more explicit about communicating our contexts better and as part of framing our presentations, to support discussions and viewpoints better. This also became apparent at the end of Mikkel Frost’s talk, where no mention of sustainability or low-energy design was made about Cebra’s projects, yet when asked about this, he clarified that the Danish building regulations are so advanced that new buildings are all low energy now and that this aspect is now so normal for them that it is easy to forget to mention these aspects in the Danish context. Yet this is far from the case in other EU countries, where we are still discussing how to achieve higher fabric standards (which was partly focus of my talk, but I too had assumed this applied to most other EU contexts!). Indeed, it is easy to forget our own contextual positions. Associate Professor Michael Asgaard Andersen from the Aarhus Architecture School on the other hand specifically drew out the Danish context related to recent thinking about resources and design for disassembly. He also reminded us of architecture’s timeline, and that what we think of today as a solution for “the future” may not be the case, and in fact may cause obsolescence or challenges later on.

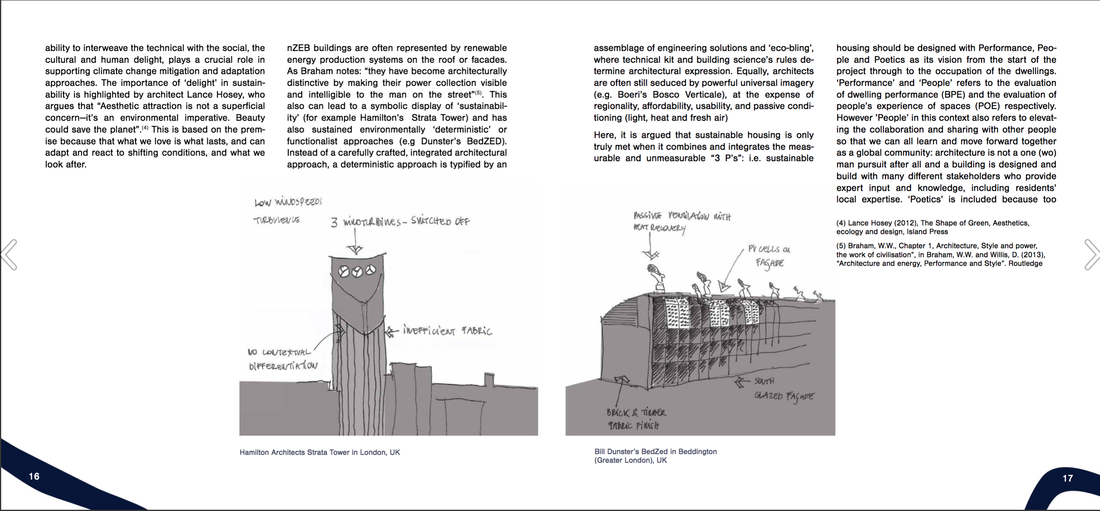

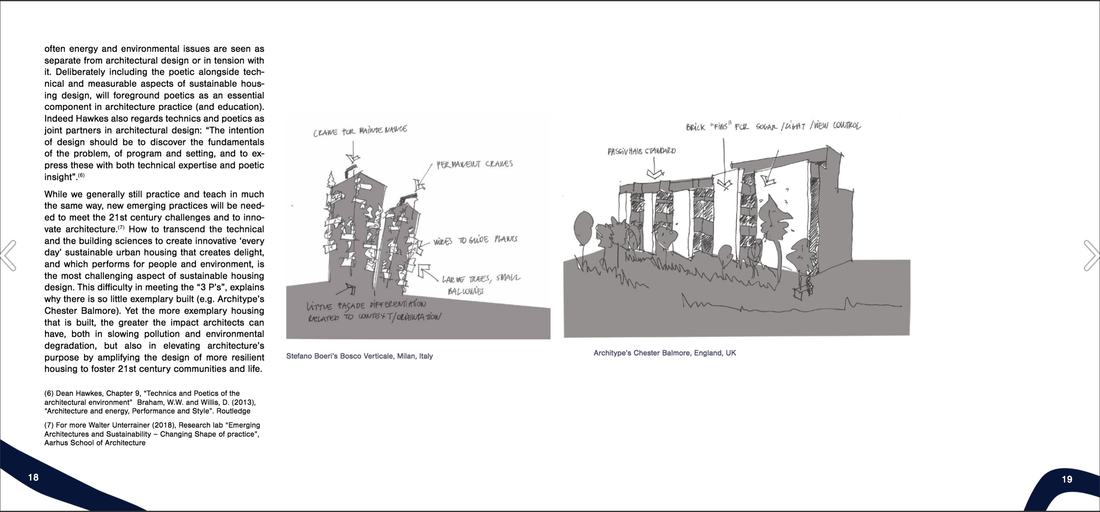

There was unfortunately insufficient time for a larger conference discussion, but this definitely made for conversation starters during breaks and social events! And it are discussions such as this that are so important to have and hopefully creates a new understanding and solidarity, acknowledging the differences in the backgrounds within which we all operate and how that this influences practice, research and the debate about housing quality. Finally, I also thought that so much good work goes on in architecture practice, but is often not explicitly stated (unless attending events like this). For example Anders Tyrrestrup, founding partner at AART Architects in Denmark talked about how they regularly invest in, and work with an independent anthropologist to evaluate user satisfaction post-building completion. They are interested in documenting the impact they make through their architecture by trying to understand how projects work in use and the value that their architecture has brought to people’s lives. Equally they have spent time with user groups prior to designing projects, yet these exemplary research-based aspects and design processes remain typically invisible to outsiders. My own talk was about sharing ideas about “Creating truly sustainable future urban housing: a new paradigm for architectural practice and teaching”, where I looked at the symposium themes through a sustainability ‘lens’, both illustrating and challenging current architectural practices and the role of the architect in the creation of sustainable urban housing. The presentation focused on the implications for both architectural expression and the role of architects in meeting environmental and energy challenges, illustrating the ongoing tension between ethics and aesthetics in sustainable housing design. Four exemplary UK projects were shared, and I put forward the idea that for housing to be truly sustainable, we need to put ‘People, Performance and Poetics’ in the foreground of our designs. You can follow some of the live talks/discussion on #alvaraaltosymposium and #alvaraaltosymposium2018. You can read our chapters, summaries of our talks here. My writing is below. |