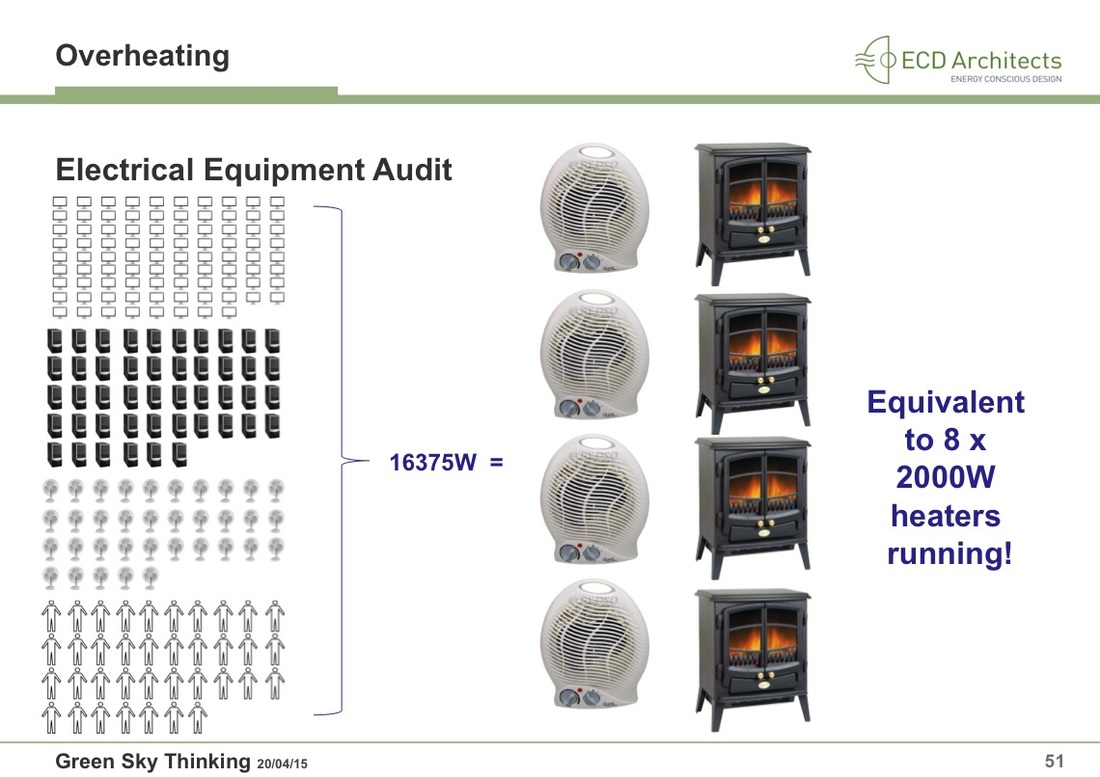

This piece was first published online by Architects Journal on April 21st and then at the UCL Energy Institute blog website. For Green Sky Thinking 2015, ECD architects presented the initial findings of a detailed Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) and Building Performance Evaluation (BPE) of their own offices. The POE was led by Carrie Behar, a doctoral researcher at the Bartlett, UCL Energy Institute, where she also runs the POE module for MSc students. A Building Use Studies (BUS)was undertaken with almost all of the 45 ECD and Keegans staff taking part in the survey and focus groups, alongside some limited monitoring of internal conditions in different locations and energy use analysis. The offices are located in a former warehouse which was converted 15 years ago, and which ECD have occupied for the last 10 years; over this period the office has grown to accommodate almost twice as many staff. User feedback highlighted several issues and the difficulty of working in an open plan office (noise), lack of space and that most of the office is too hot all year round, even in winter, with some staff complaining that this affected concentration levels. Actual data collection confirmed the high temperatures in the open plan offices, highlighting that during winter, temperatures were above CIBSE office comfort benchmarks. Further analysis has shown that this overheating is caused by a combination of factors including the building’s characteristics and high internal heat gains from the number of people and the equipment they use, as illustrated by the diagram below. It also appeared heating may not be entirely switched off at the weekend. Diagram showing equipment and people, contributing to high internal heat gains. In response, ECD intends to review energy management and control and thermostat settings in addition to making incremental changes such as arranging desks better to suit individual preferences as well as investigating passive design measures to the building such as solar shading and night cooling to prevent summer overheating. It seems that initial solutions may be straightforward and at little cost, yet with potential significant gain to occupant satisfaction and comfort. All of the above will be followed up by continuing evaluation and feedback and James Traynor, Director of Architecture at ECD Architects, intends to give an update at next year’s Green Sky Thinking week. An interesting discussion with the audience followed, where more stories (and some solutions) were shared. A few other themes appeared:

0 Comments

"This culture of post-construction disengagement needs to change and the industry needs to recognise under performance". [this comment piece first appeared in AJ, June 2013]

The Architects’ Journal Bridge the Gap campaign is a timely effort to mobilise architects and the wider industry to address the under performance of so many of our buildings. Many architects are unaware of large disparities between new buildings’ predicted performance and their actual performance. Most architects probably do not even know what the predicted energy use is of the building they designed because modelling is outsourced to other consultants, let alone what the actual energy use turns out to be. Usually architects do not return to evaluate their buildings once they are commissioned and occupied. The majority of architects are not particularly interested in finding out about their buildings’ performance, nor do they usually get paid to do this. One reason may be that PII providers do not encourage it. Why go back to evaluate your design when you may find problems and get sued? The addition of an ‘In Use’ workstage in the new RIBA Plan of Work is a step in the right direction. This culture of post-construction disengagement needs to change. The industry as a whole must recognise this underperformance. The ‘design-modelling- construction- in-use’ feedback loop is invaluable because it allows us to reflect on our mistakes. This learning process – both individually and, if made public, can prevent the repetition of mistakes. Let’s also be honest. If a building does not perform as predicted, we tend to hide this news in silence. I applaud the Bridge the Gap campaign as a way to encourage transparency and promote awareness and industry-wide learning about the performance gap. We need to get over the constant burying of underperformance in silence. Following on from Bordass and Leaman's masterclass in June 2013, the London Loughborough Centre for Doctoral Research in Energy demand is bringing together research students on November 22nd 2013 to discuss "saving energy in buildings: why does context matter?".

We are looking for poster and presentation abstracts from research students - submission deadline September 23rd. More info on flyer below and on the Lolo website. You can also already register for attendance (Prof Bob Lowe, Prof Kevin Lomas and Jez Wingfield are confirmed speakers) - the event is FREE to research students. PDF flyer for download. Download the full interim report / executive summary and appendices here.

Nothing surprising so far; with the following issues identified:

designed energy / carbon performance". A final report will be issued in March 2014. Bordass and Leaman's talks here on UCL Energy Institute's youtube channel.

This blog post was first published on the UCL Energy website and the London-Loughborough Centre for Doctoral training website, June 21st 2013.

On Wednesday June 12th, the UCL Energy Institute hosted Bill Bordass and Adrian Leaman, who lead ‘Building Performance: The bigger picture’ masterclass for research students. This was followed by an evening lecture by Bill Bordass: ‘Improving building performance: Sparing no expense to get something on the cheap?’ Steve Selkowitz, from Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory, briefly reported about performance gap issues from the USA via a remote link and reiterated several of the issues discussed by Bordass. Both events were set against a background of increasing recognition that the building industry’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions and to procure usable buildings are being jeopardised, caused by a whole host of reasons, briefly touched on in a previous blog. It is impossible to report back on the full day’s event in one blog, so instead I have written below about what I found memorable and of interest, including an attempt to capture the online and offline discussions on the day and following on since then. The performance gap: is it just about energy? Evidence from actual building energy use is indicating that the performance gap between predicted and actual energy use is significant: in non-domestic buildings actual energy use is - on average - 1.5 to 2.5 times as high as predicted. But it is important to realise that the gap is not just about energy, but also about usability and occupant satisfaction and comfort. Bordass’ and Leaman’s work highlights that many buildings don't work for their users, despite the higher than predicted (energy) cost. Crucially, buildings last a long time so good performance is in the national interest, yet we are bad at constructing buildings that actually work. Why are we so bad at constructing buildings that actually work? The division of construction procurement, where each stage is often undertaken by a different team, leads to a lack of continuity in building design and construction and hinders inter-disciplinary working. Inter-disciplinary teams are considered a good thing: it has the power to combine different views and expertise to unpick and better understand issues and find solutions. Worryingly, poor specification, poor quality control, poor commissioning and poor information flow appear to be endemic in the building industry. While construction related institutions require their members to understand sustainable construction; without understanding the real, actual, measured consequences, this understanding is limited and hampered. In addition, wallets are empty and corners are cut so much so that we do not get the basics right. The result is ‘dictatorial buildings’: they require too much energy to provide comfort levels and user satisfaction. Often this squandering of energy is justified by saying that renewable energy is provided. But this is very wrong and no excuse for an inefficient building. New buildings often involve new ‘hi-tech kit’, but innovation and sophistication is not about hi-tech kit; we also have to be careful not to make sophisticated buildings that are fragile. For example, automation can work in buildings for things people are not good at but are inappropriate to automate what people are good at. Unfortunately, often a ‘fit and forget‘ approach is undertaken, when in actual fact management and/or maintenance are required for operation. Also, many designers rely on the ‘habitual’ understanding of buildings (i.e. through constant use), but many buildings are not habitually used, so there can be no habitual learning. The solution is therefore designing with context and for usability with ‘affordance’, i.e. the ability to do things easily. When designing to context, allowance is needed for buildings to be robust changing contexts: buildings are here for a long time and need to be able to adapt/change with time. The role of Facilities Managers Corporate management of companies are interested in ‘productivity’ and how this is influenced by the interaction between people and buildings. But Bordass and Leaman warned that this should be approached with care, as productivity is just one measure of the bigger picture of how a building performs and people’s responses to the building environment. Interestingly, from their work on a small sample of 20 buildings, Bordass and Leaman found that a significant variable was a motivated facilities manager: A badly performing building may perform better with an engaged and enthusiastic facilities manager. (Though presumably a good Facilities manager may not turn a ‘bad’ building into a ‘good’ performing one?) This sparked an interesting on- and off-line discussion about housing and smaller buildings without facilities managers: if motivated facilities managers can make a bad performing building more forgiving, what does this mean for buildings that do not have building managers at all? Some argued that home-owners are after all ’facilities managers’ in their home; while Carrie Behar pointed out that “dwelling-occupants have different motivations to facilities managers” […] we cannot expect them to constantly think about energy”. Bordass briefly referred to this in his evening talk: “will ordinary people be able to look after buildings when there is complex technology? Meanwhile this complexity has spread to housing.” The role of architects/designers Facilities managers are not the only ones able to influence building performance; so can architects through their building design and by being mindful of the 'human factors' affecting building energy use. Architects however got criticised for their lack of engagement with building energy use and that they only seem concerned with ‘design’. The RIBA had an ‘in -use’ Workstage in the Plan of Work until 1972. But as clients did not seem interested this workstage was considered redundant and then completely removed from the procurement process. The ‘In-Use’ Workstage has since been reinstated in the 2013 RIBA Plan of Work (Stage 7). Bordass’s and Leaman’s outlook was pessimistic however and predicted that if the culture of disengagement with building performance does not change, then the RIBA in-use workstage won’t mean anything and won’t change anything. This current prevailing culture of disengagement is summed up by Prof. Stevenson’s tweet: “architects design, see their buildings get built, but do not check if design expectations met. They move on to the next one.” Others pointed out that this is not just architects’ fault, but lack of Client interest and willingness to pay to undertake this work. Clearly, if buildings are part of problem, they need to be part of solution. But if we don't understand them, how can we improve them? At the same time the industry often buries bad news, and looks for good examples, yet the ‘bad’ examples are ‘good’ to learn from! The role of Researchers/Academics Bordass reiterated again that while we (i.e. researchers/engineers/architects etc.) are great at achieving energy savings in the virtual world, it ultimately is about how things perform in the real world, not how they are ‘supposed’ to perform. They also said that is crucial that academic research is related to the real-world and to industry, which Bordass argued was often no longer the case. Is a 0% gap possible and should we focus on this? Energy use in buildings has many variables. We should focus on these to better understand and improve, but even this will not lead to a ‘zero’ gap between design intent and actuality. Though as the gap closes and our understanding increases, a variable for ‘in-use’ could be included at the predicted stage. Part L 2013 Bordass closed by saying that he hoped there would be no Part L 2013 improvements. His view is that the industry has enough to deal with first to get right. I am not sure I agree with this: it would be rewarding ourselves for doing badly. But I seem to be in the minority on this view going on the AECB Facebook page. One AECB member, Jake White, even started a government e-petition calling on government to “Address the performance gap in low carbon buildings before setting higher performance standards“, which you can sign here. However, Ken Neal thinks Part L step changes should stay on course as planned and sums it up well: “A drop in designed performance on a higher standard is better than a drop in performance on a lower standard. Let's not drop our vision for the future but build on what we can achieve.” Bridging the gap Some points to move forward and help the industry bridge the gap, include: 1. Review and change of construction procurement processes: Interventions are required at different stages in the construction process to reduce the performance gap. 2. Keep it simple! 3. Building management: do not build what you cannot afford to maintain and manage 4. Make performance visible, with intended and achieved performance. DECs are a start 5. Policies needs to converge instead of conflict with in-use performance 6. There is need for a new professionalism: professionals need to engage (at an individual but also collective level) with building performance. A review is needed of professional ethics and practice. 7. Do we need a ‘Building Use’ or ‘Building Performance institute’? 8. Lastly, acknowledge that Energy efficiency is a ‘wicked problem’. This term indicates the problem of energy efficiency as particularly complex, fragmented and involving many different stakeholders, as identified by the Centre for Sustainable Development; Energy Efficiency in the Built Environment (EEBE)Research Programme, Cambridge University On a personal note, it struck me that while we think we may know all the answers and solutions, it became apparent from discussions with different people, that we do not all agree nor can we say for definite what will work and whether or not trying to fix something will reveal or lead to other unintended consequences in the process. It is indeed a ‘wicked problem’! Moving forward: November 2013 At the London Loughborough Centre for Doctoral Training (LoLo CDT) we now intend to continue this debate with a gathering of research students (both presenting and attending) in November. I particularly enjoyed the presentations by some of the Doctoral researchers (Carrie Behar, Sam Stamp, David Veitch and Faye Wade), which gives a taste of research undertaken at the UCL Energy Institute/Lolo CDT and its relevance to the industry and building energy performance. So save this date in your diary: Friday 22nd November 2013 from 10am - 5pm. More details to follow. Recent related events and publications include: Bordass also spoke at the Building Centre’s/Buro Happold’s ‘Mind the Gap’ event, alongside UCL Energy Institute Prof Bob Lowe; the Architects’ Journal ‘Bridge the Gap campaign’ was launched this Spring; while the launch of the RIBA/CIBSE/UCL Carbon Buzz platform took place just earlier this month. Additionally, there was the announcement of the CIBSE 2014 Building Performance Awards, based on actual building energy performance not design intent, while the Passivhaus Trust awards also work along similar principles. Furthermore, the Institute for Sustainability published a freely available guide to Building Performance Evaluation, while earlier on in the year, the Zero Carbon Hub announced its ‘Designed v As-Built (DvAB) research’, particularly related to the performance gap in dwellings, which follows on from the NHBC’s 2012 report ‘Low and zero carbon homes: understanding the performance challenge (NF41)’ Earlier this month, Christopher Gorse from LeedsMet wrote on ‘Closing the Performance Gap’ at STN News while this week UKGBC Pinpoint is undertaking a discussion on BSRIA’s Soft landings framework and AECB members are adding their weight on online discussion forums and by setting up a petition. The Government’s Soft Landings policy :”Post Operational Evaluation will be used as a collaborative tool to measure and optimise asset performance and embed lessons learnt.” This is proposed to apply to all new and major refurbishments in Central Government during 2016. 1. Free access to Soft Landings guidance for clients, users and architects to set expectations and performance targets on energy and end-user satisfaction from inception to completion.

2. Usable Building Trust, dedicated to improving building performance by understanding how buildings perform in use and how this can feedback in building design. Some really useful publication links. 3. Institute for Sustainability guide to Building Performance Evaluation (BPE) in retrofits, with simple 'in-use BPE' here and recommended detailed in-use investigations here and specialist testing for major retrofits. General site here, includes guidance for domestic and non-domestic. 4. The AJ's Bridge The Gap Campaign and performance gap info. 5. Carbon Buzz has several case studies of buildings' predicted and actual energy use, and you can upload your own projects too. Write up of the launch event here. 6. AECB Soapbox - Paul Buckingham on construction problems leading to performance gap. 7. AECB member Jake White has started a government e-petition calling on government to “Address the "performance gap" in low carbon buildings before setting higher performance standards." 8. Historic Scotland has freely available research on the in-situ performance of existing building structures, highlighting that assumed U-values in RdSAP and literature may overestimate heatloss from traditional pre-1919 building fabric. 9. Carbon Trust document on Closing the Gap and by Gary Clark in AJ. 10. Courtesy of Elrond Burrell: The Government’s Soft Landings policy:”Post Operational Evaluation will be used as a collaborative tool to measure and optimise asset performance and embed lessons learnt.” This is proposed to apply to all new and major refurbishments in Central Government in 2016. 11. Roger Hunt writes about the performance gap too in ShowHouse. 12. The Building Centre’s/Buro Happold’s ‘Mind the Gap’ event, 13. The CIBSE 2014 Building Performance Awards, based on actual building energy performance not design intent, while the Passivhaus Trust awards also work along similar principles. 14. The Zero Carbon Hub announced its ‘Designed v As-Built (DvAB) research’, particularly related to the performance gap in dwellings, which follows on from the NHBC’s 2012 report‘Low and zero carbon homes: understanding the performance challenge (NF41)’ 15. Christopher Gorse from LeedsMet wrote on ‘Closing the Performance Gap’ at STN News while this week UKGBC Pinpoint is undertaking a discussion on BSRIA’s Soft landings framework. Discussion here. 16. Kate de Selincourt recommended following articles ( and also have a look at the first blog post as further reading there too):

17. Courtesy of Rory Bergin - Initial Retrofit for Future analysis report 18. " Should We Expect Energy Modeling to Predict Building Performance?"o or "The real value of modeling is not predicting energy use but making relative comparisons among design options" and also here. 19. 'People do matter' --> write up by Nic Combe of CIBSE YEPG event. 20. AJ's Performance Gap panel reports back. (Aug 1st 2013) 21. Rory Bergin on what he thinks Performance gaps reasons are. (Aug 2013) 22. Zero Carbon Hub's preliminary findings can be downloaded here; and summary of main findings here. 23. CIBSE TM54 Evaluating Energy Use at the Design Stage is a guide - due later in 2013 - to enable designers to make better operational energy use predictions. (Calculations used for Part L compliance are not appropriate to predict operational energy use.) 24. CIBSE PROBE studies (POE). My blog post below has appeared in an edited version in the Architects' Journal, June 11th 2013.

An edited version of the below blog post has also appeared on the Architects' Journal's website here June 10th 2013. The Architects’ Journal’s ‘Bridge the Gap’ campaign is a timely and highly commendable attempt to mobilise architects and the wider building industry to address the underperformance of so many of our buildings, and what we can – individually and collectively - do about this.

Many architects seem unaware that large disparities exist between new buildings’ predicted performance and their actual, real performance.(1-3) This means buildings are more costly to operate than predicted, while also having a greater environmental impact than intended. So far, a variety of reasons have been identified for this performance gap, such as construction errors and the use of inaccurate modelling tools.(4) Additionally, occupant behaviour itself is known to significantly influence energy demand, for instance through how many rooms are heated, thermostat settings and heating duration, opening of windows and how and – whether or not- building systems are at all used or correctly used.(2, 5-10) Many low energy buildings increasingly rely on complex building systems, increasing the opportunity for things to ‘go wrong’. Clearly, to achieve the ambitious energy reductions required, it is essential that actual energy reductions meet calculated, predicted reductions.(10) Let’s also be honest: if a building does not perform as (well as) predicted, we tend to hide this news in embarrassed silence. In fact, a bigger problem exists before we even consider this issue: usually architects do not go back and systematically evaluate the buildings they designed to see how they perform once commissioned and occupied. One reason may be that PII providers do not tend to encourage it (“why go back to evaluate your design when you may find problems and get sued”). But as a profession, architects do not seem to be very interested either in finding out their buildings’ performance, nor do they usually get paid to do this. In fact, most architects probably do not even know what the predicted energy use is of the building they designed (modelling is usually outsourced to other consultants), let alone what the actual energy use turns out to be. This culture of pre- and post-construction disengagement needs to change - drastically. It is long overdue that the building industry as a whole recognises its underperformance. The ‘design-modelling- construction- in-use’ feedback loop is invaluable as it allows us to obtain building and user feedback to reflect on and learn from our mistakes. This learning process – both individually and – if made public - the whole building industry– can then prevent those same mistakes in future building-design and construction. The addition of an ‘In Use’ workstage in the new RIBA Plan of Work, which “acknowledges the potential benefits of harnessing the project design information to assist with the successful operation and use of a building” (11) is clearly a step in the right direction. The concern for buildings’ in use performance is also echoed by the Architects’ Journal’s ‘Bridge the Gap‘ campaign. This campaign aims to support individual and industry-wide reflection and learning, as opposed to the constant pretence that the performance gap does not exist or the constant burying of underperformance under silence. In so doing, the campaign also raises a crucial question: what is the architect’s and architectural profession’s role and responsibility in bridging this performance gap? If we stop pretending that the performance gap does not exist, and if we stop burying underperformance under embarrassed silence, what is the worst that can happen? I believe that we only have to gain: a reflective and reflexive building industry, learning how to build better and predictable buildings for our clients, its users and the environment. And, how bad can that really be? Notes/references 1. Leaman A, Stevenson F, Bordass B. Building evaluation: practice and principles. Building Research & Information. 2010;38(5):564-77. 2. Stevenson F, Leaman, A. (editors). Special issue: Housing Occupancy Feedback: linking behaviours and performance. Building Research & Information. 2010;38(5 Sept-Oct 2010). 3. Mumovic D, Santamouris, M. . A handbook of Sustainable Building Design & Engineering. An Integrated Approach to energy, health and operational performance. London: Earthscan; 2009. 4. LeedsMet. AIRTIGHTNESS OF UK HOUSING. LeedsMet; 2009 [cited 2012 April 10th]; Available from: http://www.leedsmet.ac.uk/teaching/vsite/low_carbon_housing/airtightness/housing/index.htm. 5. Barrett M LR, Oreszczyn T,Steadman P. How to support growrh with less energy. 2006. 6. Audenaert A, Briffaerts K, Engels L. Practical versus theoretical domestic energy consumption for space heating. Energy Policy. 2011;39(9):5219-27. 7. Guerra Santin O, Itard, L., Visscher, H. The effect of occupancy and building characteristics on energy use for space and water heating in Dutch residential stock. Energy and Buildings. 2009;41(11):1223-32. 8. Guerra-Santin O, Itard, L. Occupants' behaviour: determinants and effects on residential heating consumption. Building Research & Information. 2010;38(3):318-38. 9. Guerra Santin O. Behavioural Patterns and User Profiles related to energy consumption for heating. Energy and Buildings. 2011;43(10):2662-72. 10. Summerfield A, Oreszcyn, T., Pathan, A., Hong, S. . Occupant Behaviour and energy use. In: Mumovic D, Santamouris, M., editor. A handbook of Sustainable Building Design & Engineering An Integrated Approach to energy, health and operational performance. London: Earthscan; 2009. 11. RIBA. RIBA 2013 Plan of Work 2013; Available from: http://www.ribaplanofwork.com/PlanOfWork.aspx. |

AuthorThis is Sofie's blog; or rather a collection of musings & articles sometimes also published elsewhere. More about Sofie here. Archives

May 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed