Franco-British bilateral conference on Climate Change Adaptation, Resilience & Risks

On June 2nd, UCL and the French Embassy in London held talks and workshops for invited ‘millenials’ and UCL postgraduate students discussing future climate change adaptation to focus on how both countries and their capital cities are going to adapt to climate change challenges and how to increase resilience to climate change risks (you can watch here). This was followed by a public debate, hosted by the BBC’s environment correspondent Roger Harrabin. I had to miss the latter as I was attending the RIBA Role Models Project launch as written about here

Doctor Ian Scott and the UCL Grand Challenges team had managed to get several high-profile speakers around the table:ChrisRapley CBE, Professor of Climate Science at UCL who chaired the discussions and workshops; Hervé le Treut, Senior Researcher, French National Centre for Scientific Research, Dynamic Meteorology Laboratory; John (Lord) Krebs FRS, UK Committee on Climate Change Adaptation Subcommittee; Professor Nicolas Beriot, Secretary General, National Observatory of Climate Warming Effects, Ministry of Ecology, Paris; Claire Vetori, Environmental Advisor to Thames Estuary Asset Management 2100 team; Professor Tim Reeder from the UK Environment Agency; Célia Blauel, Deputy Mayor, City of Paris (Environment, Sustainable Development, Water, Climate Plan portfolio); Alex Nickson, Strategy Manager for Climate Change Adaptation and Water, Greater London Authority,Professor Mike Davies, Director of the UCL Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering, Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment.

First, UK and French experts gave short presentations setting out climate change facts, risks, threats and solutions. We were reminded about sea level rises which are geologically significant; that predictive models are coinciding with real world patterns though there are uncertainties in models so we don’t know how exactly it will change. UCL’s Professor Mike Davies set out health effects of increased summer temperatures and increased exposure to particulate pollution when relying on purge ventilation to achieve summer cooling. Regularly similarities between France and the UK were drawn out: heatwaves and their impact on older people and excess death is especially a reality in both countries and their capital cities. Lord Krebs and Professor Tim Reeder stressed that the top risk in the UK is flooding and that we are increasing our risk in the UK by building at a faster rate in floodplains than ever before as well as paving over with hard surfaces in urban areas – so we are storing up future problems such as flash floods leading to increased insurance claims from local flooding. At the same time we will have too little water at other times.

While in the UK we have a National Adaptation Programme (NAP)along 7 themes (e.g. business/ natural environment and built environment), which are broken down in many more objectives and hundreds of individual actions, there is a lack of priority and no means to measure their effectiveness.

Célia Blauel, the Deputy Mayor of Paris, discussed how Paris faces similar issues as London in protecting people from increasing summer temperatures but that the Parisian water infrastructure is – while old – considered robust. In Paris, overheating and drought, not flooding, are the main issues. Paris has a Green Climate Fund to support other cities on climate adaptation and has several schemes to help citizens organise mitigation and adaptation projects. Much of Paris’ projects focus on sharing issues and solutions with citizens on how to make changes in every day life with a focus on the long term good of it and co-benefits.

We then split in small groups to discuss a particular topic – Sofie was in the workshop benefitting from expertise and input from Lord Krebs, and Célia Blauel, Deputy Paris Mayor and Professor Tim Reeder from the UK Environment Agency (EA) – where we were asked to discuss the most important areas for public engagement. Our workshop was chaired by Benjamin Gower.

Lord Krebs said that there is a role for traditional marketing in mobilising and engaging the public and gave the i-phone example: so many of us bought it not because we need it but because others have it. We need to present information; raise awareness, incentivise; do it because everyone else does; use of nudging principles: nudging people to make change by choice architecture?

Tim Reeder raised that putting information out there is not enough; that we need to sell a solution and sneak this into a mindset. But, as Lord Krebs pointed out, the UK EA is responsible for raising awareness to business and organisations, but not to the public. Lord Krebs said he had asked this question in Parliament and also how much money is spent on public awareness of climate change and its risks; shockingly, the answer is nothing! So in the UK it appears there is no vision and no leadership how to deal with such pressing issues and how to engage the public. Yet we all felt that the public expects the government to act.

But as Tim Reeder pointed out: politicians themselves do not even seem aware of the scale of the problem, let alone tell the public about it. Célia Blauel also said there is a similar problem in France with not much wider vision from government, though Paris is trying to take the lead on climate action but as always finance is missing to implement. It was felt that focus on co-benefits of acting on climate change would be a better way to engage the public (such as reduced bills, better comfort and health) rather than on CO2. Much emphasis on local cooperation, regional approaches and involving local communities and people; though there is an issue of widening local initiatives to a country level: there seem many interesting community and street-by-street projects but they often stand on their own and are not rolled out on a larger scale so their impact on the whole is minimal. How to ‘mainstream’ this? How to use these projects to raise wider awareness? ICLEI, the EU International Council for Local Environment Initiatives, intends to network the success of cities and their citizens – but is this enough and does it reach enough people? People live in cities and mayors and local authorities connect more effectively with their citizens than at national level so cities can be a powerful way of working with citizens.

Key themes that appeared for me in our discussion group were:

It was clear that an end is needed to the separation of climate change mitigation and adaptation and that we are not prioritising the way we should: adaptation and mitigation are framed in a cost-benefit trade off, instead of asking ourselves what kind of society we want? What price tag do we put on a flooded community or a lost life? Cities have a unique position at COP negotiations as the majority of people live in cities.

The discussions were ambitious and recognised the importance of a bottom-up approach. On the other hand, I could not stop feeling that the scale of the challenge ahead requires for a larger change and different tactics so far used than just soft measures from some individuals, a few progressive towns or communities. For example, in the UK, we need to improve the housing stock by upgrading one house every minute of the day until 2050 to high standards. As upgrading our housing stock is mostly left to individual homeowners and a few city or community schemes, with no large scale roll-out or legislation or significant incentives we are not seeing the scale of upgrade required to bring about change.

Anna participated in a workshop chaired by Yasmine Svan Saarela that brought together experts from both the UK and France, such as Alex Nickson from the Greater London Authority and Professor Nicolas Beriot from the French Ministry of Ecology. We were asked to explore the meaning of the concepts of ‘cost’ and ‘value’ in the context of a changing climate. Our discussion primarily revolved around the challenges associated with assigning a value to climate change resilience. Whilst there are various metrics for economic costs such as, for example, the cost of insurance payouts due to weather-related business disruption and NHS on-costs as a result of increased climate-related health burdens, is it possible to monetise the value of quality of life?

During our discussion, a consensus was reached that we should be focusing on the value rather than the current price of climate resilience. Understandably perhaps, valuing climate change adaptation may be difficult for individuals because it is contingent upon abstract future threats. A frequent underlying assumption in our models and studies is that of rational human behaviour; nevertheless, this may not apply to individual actions and choices that have a bearing on climate change mitigation and adaptation. It was hypothesised that, unfortunately, a ‘game-changer’ excess weather event, such as the Paris 2003 heatwave or the Copenhagen 2011 floods, would be required to increase public awareness, leverage new technologies and mobilise effective action towards building resilient cities.

Public debate summing up

The afternoon public debate was opened with welcome remarks by Professor David Price, UCL Vice-Provost

Research. BBC’s Roger Harrabinintroduced the debate and the speakers by highlighting the urgent need to build cities that do not add to climate risk. He also pointed out the fact that the word resilience has come to the fore. Is it a more appropriate word than adaptation, however?

HE Sylvie Bermann, Ambassador, Embassy of France in the UK, gave a brief talk on COP21 and the French perspective. Climate change is a global issue that brings us together. Combating climate change requires solidarity at national and global levels; business understands urgency. This is of vital importance as the least developed countries are most at risk while not being able to rely on technological advances and other resources. However, climate adaptation is a crucial issue in developed countries as well. The people already facing the impacts are at the forefront. On the 21st July, France’s ethical and religious figures will be calling on world leaders to take action on climate change. Once more it was pointed out that France and the UK share the same proactive approach towards climate adaptation and mitigation.

Following up on this last point, Célia Blauel emphasised the importance of learning from each other. Cities and Local Authorities have a major role to play in building climate resilience. She stated that we already have the tools needed to act and ways to engage with citizens at the local scale. Currently, adaptation is not widely understood by the wider public: we need to move from abstract IPCC definitions to reality. She identified 3 key themes in relation to the vulnerability of Paris in the face of climate change:

The two keynote talks were followed by a summary of the earlier workshop findings by Professor Chris Rapley. Quoting Winston Churchill, he stated that ‘we are entering a period of consequences’. Even if a legally binding target is set at COP21, this is only the beginning of a major effort. Climate change is with us; even if negotiations are successful, there is more climate change down the pipeline. Making decisions under irreducible uncertainties is a major challenge. We need to reframe individual and government actions in terms of resilience and adaptation pathways. Cities will have a vital role to play in this because they are conglomerations where the connections between individual and instruments of governments are stronger, thus generating greater traction, citizen involvement and co-creation of ideas and solutions. It was emphasised that it is not a good idea to scare people! We should inspire them to see this as an act to construct a better future. This pertains to the idea that we can learn from indigenous cultures, in particular in the Global South. Our action plans should be characterised by a generosity of thought and transfer of ideas. Unfortunately, institutions that have pursued globalisation are disconnected from UN carbon reduction efforts. Integration is needed.

This session was followed by panel discussion. The panel comprised Célia Blauel, Professor Nicolas Beriot, Professor Mike Davies, Professor Lord John Krebs, Alex Nickson, Professor Hervé le Treut and Professor Tim Reeder.

Parallels were drawn between the climate risks faced and the adaptation approaches adopted in London and Paris. Co-operation between cities around the world is essential in order to move faster and better. Alex Nickson discussed the need to identify ‘triple jeopardy’ hot spots in the city by overlaying different layers of vulnerability: (i) heat vulnerability related to the location of a building within the urban heat island location, (ii) the physical properties of the building, and (iii) individual vulnerability of the occupants (age, health status etc.). Professor Nicolas Beriotreminded us that we first need to adapt to the present. We need to seek creative pathways to adaptation, such as biomimicry. Professor Mike Davies discussed the need for a holistic approach towards mitigation and adaptation that identifies and prevents unintended consequences. We need to ensure that technological applications are appropriate to the lifestyle and the vulnerability of inhabitants. Hervé Le Treut suggested that adaptation is a good way to introduce people to what is climate change and mobilise them.

Join the conversation tweet Sofie Pelsmakers

#ClimateParis2015

Doctor Ian Scott and the UCL Grand Challenges team had managed to get several high-profile speakers around the table:ChrisRapley CBE, Professor of Climate Science at UCL who chaired the discussions and workshops; Hervé le Treut, Senior Researcher, French National Centre for Scientific Research, Dynamic Meteorology Laboratory; John (Lord) Krebs FRS, UK Committee on Climate Change Adaptation Subcommittee; Professor Nicolas Beriot, Secretary General, National Observatory of Climate Warming Effects, Ministry of Ecology, Paris; Claire Vetori, Environmental Advisor to Thames Estuary Asset Management 2100 team; Professor Tim Reeder from the UK Environment Agency; Célia Blauel, Deputy Mayor, City of Paris (Environment, Sustainable Development, Water, Climate Plan portfolio); Alex Nickson, Strategy Manager for Climate Change Adaptation and Water, Greater London Authority,Professor Mike Davies, Director of the UCL Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering, Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment.

First, UK and French experts gave short presentations setting out climate change facts, risks, threats and solutions. We were reminded about sea level rises which are geologically significant; that predictive models are coinciding with real world patterns though there are uncertainties in models so we don’t know how exactly it will change. UCL’s Professor Mike Davies set out health effects of increased summer temperatures and increased exposure to particulate pollution when relying on purge ventilation to achieve summer cooling. Regularly similarities between France and the UK were drawn out: heatwaves and their impact on older people and excess death is especially a reality in both countries and their capital cities. Lord Krebs and Professor Tim Reeder stressed that the top risk in the UK is flooding and that we are increasing our risk in the UK by building at a faster rate in floodplains than ever before as well as paving over with hard surfaces in urban areas – so we are storing up future problems such as flash floods leading to increased insurance claims from local flooding. At the same time we will have too little water at other times.

While in the UK we have a National Adaptation Programme (NAP)along 7 themes (e.g. business/ natural environment and built environment), which are broken down in many more objectives and hundreds of individual actions, there is a lack of priority and no means to measure their effectiveness.

Célia Blauel, the Deputy Mayor of Paris, discussed how Paris faces similar issues as London in protecting people from increasing summer temperatures but that the Parisian water infrastructure is – while old – considered robust. In Paris, overheating and drought, not flooding, are the main issues. Paris has a Green Climate Fund to support other cities on climate adaptation and has several schemes to help citizens organise mitigation and adaptation projects. Much of Paris’ projects focus on sharing issues and solutions with citizens on how to make changes in every day life with a focus on the long term good of it and co-benefits.

We then split in small groups to discuss a particular topic – Sofie was in the workshop benefitting from expertise and input from Lord Krebs, and Célia Blauel, Deputy Paris Mayor and Professor Tim Reeder from the UK Environment Agency (EA) – where we were asked to discuss the most important areas for public engagement. Our workshop was chaired by Benjamin Gower.

Lord Krebs said that there is a role for traditional marketing in mobilising and engaging the public and gave the i-phone example: so many of us bought it not because we need it but because others have it. We need to present information; raise awareness, incentivise; do it because everyone else does; use of nudging principles: nudging people to make change by choice architecture?

Tim Reeder raised that putting information out there is not enough; that we need to sell a solution and sneak this into a mindset. But, as Lord Krebs pointed out, the UK EA is responsible for raising awareness to business and organisations, but not to the public. Lord Krebs said he had asked this question in Parliament and also how much money is spent on public awareness of climate change and its risks; shockingly, the answer is nothing! So in the UK it appears there is no vision and no leadership how to deal with such pressing issues and how to engage the public. Yet we all felt that the public expects the government to act.

But as Tim Reeder pointed out: politicians themselves do not even seem aware of the scale of the problem, let alone tell the public about it. Célia Blauel also said there is a similar problem in France with not much wider vision from government, though Paris is trying to take the lead on climate action but as always finance is missing to implement. It was felt that focus on co-benefits of acting on climate change would be a better way to engage the public (such as reduced bills, better comfort and health) rather than on CO2. Much emphasis on local cooperation, regional approaches and involving local communities and people; though there is an issue of widening local initiatives to a country level: there seem many interesting community and street-by-street projects but they often stand on their own and are not rolled out on a larger scale so their impact on the whole is minimal. How to ‘mainstream’ this? How to use these projects to raise wider awareness? ICLEI, the EU International Council for Local Environment Initiatives, intends to network the success of cities and their citizens – but is this enough and does it reach enough people? People live in cities and mayors and local authorities connect more effectively with their citizens than at national level so cities can be a powerful way of working with citizens.

Key themes that appeared for me in our discussion group were:

- We need to act now (or rather, yesterday): this way we benefit from resilience for longer and it will be cheaper.

- We need to allow for different pathways as we face an uncertain future. For example: to protect London under the 4 meter sea-level rise scenario is extremely expensive: does it make sense to protect the city or is it better to ‘move’ London?

- We need centralisation of a main, positive message and real vision/leadership backed up byfinancial incentives from central government, with decentralisation of the execution of solutions and engagement with local communities.

- We need to emphasise co-benefits of climate change mitigation and adaptation measures.

- We need to be careful about (unintended) consequences of climate change mitigation so people do not disengage.

It was clear that an end is needed to the separation of climate change mitigation and adaptation and that we are not prioritising the way we should: adaptation and mitigation are framed in a cost-benefit trade off, instead of asking ourselves what kind of society we want? What price tag do we put on a flooded community or a lost life? Cities have a unique position at COP negotiations as the majority of people live in cities.

The discussions were ambitious and recognised the importance of a bottom-up approach. On the other hand, I could not stop feeling that the scale of the challenge ahead requires for a larger change and different tactics so far used than just soft measures from some individuals, a few progressive towns or communities. For example, in the UK, we need to improve the housing stock by upgrading one house every minute of the day until 2050 to high standards. As upgrading our housing stock is mostly left to individual homeowners and a few city or community schemes, with no large scale roll-out or legislation or significant incentives we are not seeing the scale of upgrade required to bring about change.

Anna participated in a workshop chaired by Yasmine Svan Saarela that brought together experts from both the UK and France, such as Alex Nickson from the Greater London Authority and Professor Nicolas Beriot from the French Ministry of Ecology. We were asked to explore the meaning of the concepts of ‘cost’ and ‘value’ in the context of a changing climate. Our discussion primarily revolved around the challenges associated with assigning a value to climate change resilience. Whilst there are various metrics for economic costs such as, for example, the cost of insurance payouts due to weather-related business disruption and NHS on-costs as a result of increased climate-related health burdens, is it possible to monetise the value of quality of life?

During our discussion, a consensus was reached that we should be focusing on the value rather than the current price of climate resilience. Understandably perhaps, valuing climate change adaptation may be difficult for individuals because it is contingent upon abstract future threats. A frequent underlying assumption in our models and studies is that of rational human behaviour; nevertheless, this may not apply to individual actions and choices that have a bearing on climate change mitigation and adaptation. It was hypothesised that, unfortunately, a ‘game-changer’ excess weather event, such as the Paris 2003 heatwave or the Copenhagen 2011 floods, would be required to increase public awareness, leverage new technologies and mobilise effective action towards building resilient cities.

Public debate summing up

The afternoon public debate was opened with welcome remarks by Professor David Price, UCL Vice-Provost

Research. BBC’s Roger Harrabinintroduced the debate and the speakers by highlighting the urgent need to build cities that do not add to climate risk. He also pointed out the fact that the word resilience has come to the fore. Is it a more appropriate word than adaptation, however?

HE Sylvie Bermann, Ambassador, Embassy of France in the UK, gave a brief talk on COP21 and the French perspective. Climate change is a global issue that brings us together. Combating climate change requires solidarity at national and global levels; business understands urgency. This is of vital importance as the least developed countries are most at risk while not being able to rely on technological advances and other resources. However, climate adaptation is a crucial issue in developed countries as well. The people already facing the impacts are at the forefront. On the 21st July, France’s ethical and religious figures will be calling on world leaders to take action on climate change. Once more it was pointed out that France and the UK share the same proactive approach towards climate adaptation and mitigation.

Following up on this last point, Célia Blauel emphasised the importance of learning from each other. Cities and Local Authorities have a major role to play in building climate resilience. She stated that we already have the tools needed to act and ways to engage with citizens at the local scale. Currently, adaptation is not widely understood by the wider public: we need to move from abstract IPCC definitions to reality. She identified 3 key themes in relation to the vulnerability of Paris in the face of climate change:

- climate-related risks (heatwaves, droughts, landslides),

- scarcity of resources (water, food etc.),

- risks to infrastructure (electricity supply, transport, health and welfare).

The two keynote talks were followed by a summary of the earlier workshop findings by Professor Chris Rapley. Quoting Winston Churchill, he stated that ‘we are entering a period of consequences’. Even if a legally binding target is set at COP21, this is only the beginning of a major effort. Climate change is with us; even if negotiations are successful, there is more climate change down the pipeline. Making decisions under irreducible uncertainties is a major challenge. We need to reframe individual and government actions in terms of resilience and adaptation pathways. Cities will have a vital role to play in this because they are conglomerations where the connections between individual and instruments of governments are stronger, thus generating greater traction, citizen involvement and co-creation of ideas and solutions. It was emphasised that it is not a good idea to scare people! We should inspire them to see this as an act to construct a better future. This pertains to the idea that we can learn from indigenous cultures, in particular in the Global South. Our action plans should be characterised by a generosity of thought and transfer of ideas. Unfortunately, institutions that have pursued globalisation are disconnected from UN carbon reduction efforts. Integration is needed.

This session was followed by panel discussion. The panel comprised Célia Blauel, Professor Nicolas Beriot, Professor Mike Davies, Professor Lord John Krebs, Alex Nickson, Professor Hervé le Treut and Professor Tim Reeder.

Parallels were drawn between the climate risks faced and the adaptation approaches adopted in London and Paris. Co-operation between cities around the world is essential in order to move faster and better. Alex Nickson discussed the need to identify ‘triple jeopardy’ hot spots in the city by overlaying different layers of vulnerability: (i) heat vulnerability related to the location of a building within the urban heat island location, (ii) the physical properties of the building, and (iii) individual vulnerability of the occupants (age, health status etc.). Professor Nicolas Beriotreminded us that we first need to adapt to the present. We need to seek creative pathways to adaptation, such as biomimicry. Professor Mike Davies discussed the need for a holistic approach towards mitigation and adaptation that identifies and prevents unintended consequences. We need to ensure that technological applications are appropriate to the lifestyle and the vulnerability of inhabitants. Hervé Le Treut suggested that adaptation is a good way to introduce people to what is climate change and mobilise them.

Join the conversation tweet Sofie Pelsmakers

#ClimateParis2015

Future-proofing London

I contributed to a UCL book: Future-proofing London in: Bell, S and Paskins, J. (eds.) Imagining the Future City: London 2062. Pp. 73-83. London: Ubiquity Press and spoke about the above at the Future of London/UCL ‘London 2062 – Housing Seminar’ .

You can download the book chapter here for free. The chapter is based on Pelsmakers; 'The Environmental Design Pocketbook' and lead to other pieces of writing such as "Living with water: four buildings that will withstand flooding" for The Conversation (Feb 25th 2014). I also wrote another related piece 'REBUILDING OUR CITIES IN A WORLD FACING FLOODING' for The Architectural Review (April 2014); with a shorter printed version 'Apres moi, le deluge' (pdf, page 27). Kevin Hartnett at the Boston Globe (also here) and 'Cities on frontline of climate change struggle' also picked up on the issues raised. There is also a short video interview here by UCL; a blog for UCL's Climate Week (2014) and a blog that first appeared at ECOWAN below.

You can download the book chapter here for free. The chapter is based on Pelsmakers; 'The Environmental Design Pocketbook' and lead to other pieces of writing such as "Living with water: four buildings that will withstand flooding" for The Conversation (Feb 25th 2014). I also wrote another related piece 'REBUILDING OUR CITIES IN A WORLD FACING FLOODING' for The Architectural Review (April 2014); with a shorter printed version 'Apres moi, le deluge' (pdf, page 27). Kevin Hartnett at the Boston Globe (also here) and 'Cities on frontline of climate change struggle' also picked up on the issues raised. There is also a short video interview here by UCL; a blog for UCL's Climate Week (2014) and a blog that first appeared at ECOWAN below.

London 2062: where to start? Let’s face it; it is impossible to predict how our cities might change over the next 50 years, but we can speculate about what might happen if the UK, combined with other countries globally, failed to meet carbon reduction targets. Globally we are on a trajectory to medium or high global warming, and there is no evidence to the contrary that this will change. Consequently, this means a 2-6ºC rise by 2100, and while this blog will focus on the implications of this rise on London, cities all over the world will face adaptation issues – some similar to London, others entirely different. Let’s start with the climate change predictions. By 2080, London’s summers are expected to be as warm as the Mediterranean climate of Marseille, but without the extra sun-hours. While some consider this ‘good’ news, the reality is that our urban and built environment is not built to cope with such weather. For example, in the 2003 heat wave, the UK alone counted 2000 heat-related deaths, while Europe suffered thousands more. While a 3-4ºC increase in winter temperatures undoubtedly cuts winter fuel poverty, a similar summer temperature increase is likely to lead to summer ‘cooling’ poverty – when the elderly in particular will struggle to cope in ill-adapted homes.

© The Environmental Design Pocketbook - Map of UK cities and predicted 2080 future summer temperature 'sister cities'.

Additionally, sea levels are expected to rise by as much as 900 mm, and although annual rainfall is not predicted to change, it is the distribution of rain which will become problematic, with up to a third more rain falling in winter and nearly equivalent decreases in summer. Water problems are already being witnessed in London and elsewhere in England, as evidenced by the ‘hosepipe ban’ coming into force this month.

However it is not all bad news. While the predicted weather conditions will be new to the UK, they are already a fact of life for much of the world and building precedents in Mediterranean countries could teach us how to adapt our cities to cope with increased summer temperatures. Similarly, the Netherlands is a country with more than 50% of its landmass below sea level and can teach us how to work with water, rather than against it.

However it is not all bad news. While the predicted weather conditions will be new to the UK, they are already a fact of life for much of the world and building precedents in Mediterranean countries could teach us how to adapt our cities to cope with increased summer temperatures. Similarly, the Netherlands is a country with more than 50% of its landmass below sea level and can teach us how to work with water, rather than against it.

Flood-proof housing in the Netherlands & Venice, a ‘floodable’ city with solar protection. © Pelsmakers

While we can only speculate about how things will change and how ‘bad’ they may get, we can and should future-proof our buildings today by undertaking adaptation measures, which simultaneously support climate change mitigation efforts. Here are my simple top 5 key adaptation and mitigation measures to undertake, for both new-build as well as retrofit of housing:

1. Insulating & increasing the airtightness of buildings helps buffer against cold winters and is also effective in assisting with warmer summers.

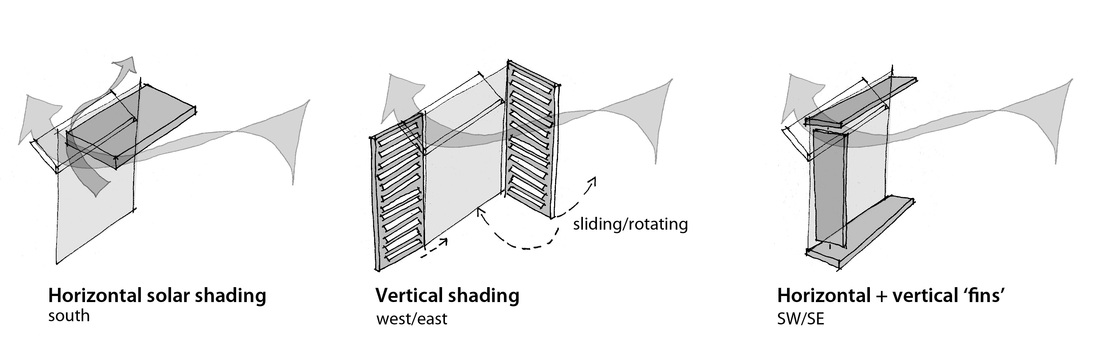

2. Incorporate sliding or inward-opening windows, which allow external solar shading to be closed, while allowing good natural ventilation (see also 3).

1. Insulating & increasing the airtightness of buildings helps buffer against cold winters and is also effective in assisting with warmer summers.

2. Incorporate sliding or inward-opening windows, which allow external solar shading to be closed, while allowing good natural ventilation (see also 3).

©The Environmental Design Pocketbook – inward opening windows with solar shading, allowing good, secure night ventilation through small top-opening windows.

3. Ensure good night-cooling and cross ventilation, while blocking unwanted summer-sun out. Thermal mass may also play a role in buffering against high summer-time temperatures as long as good, secure night cooling is provided to release built-up heat from the daytime. Failure to do so may cause overheating.

4. Increase greenery, permeable surfaces & water storage – both at micro and macro scale. These measures will help London and many other cities deal with increased risk of localised flash floods and also the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, which exacerbates summer overheating. Green spaces and water squares, which collect rainwater and act as an amenity for city-dwellers, can help reduce local summer temperatures by creating a ‘park cool island’ effect, with temperatures 2–3°C lower than the surroundings. The larger the green space, the greater the tempering effect, although this effect can still be felt with small spaces too.

5. Finally, provide light coloured external surfaces at micro & macro scale. Vernacular architecture in warmer countries show that light and reflective surfaces, when used on buildings and streetscapes, can keep buildings cooler and reduce surface temperatures by 10–20°C.

4. Increase greenery, permeable surfaces & water storage – both at micro and macro scale. These measures will help London and many other cities deal with increased risk of localised flash floods and also the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, which exacerbates summer overheating. Green spaces and water squares, which collect rainwater and act as an amenity for city-dwellers, can help reduce local summer temperatures by creating a ‘park cool island’ effect, with temperatures 2–3°C lower than the surroundings. The larger the green space, the greater the tempering effect, although this effect can still be felt with small spaces too.

5. Finally, provide light coloured external surfaces at micro & macro scale. Vernacular architecture in warmer countries show that light and reflective surfaces, when used on buildings and streetscapes, can keep buildings cooler and reduce surface temperatures by 10–20°C.

Light-coloured surfaces to reflect solar radiation and trees to provide shade in Avignon, France. © Pelsmakers

Of course, future-proofing means that, while certain measures can be implemented later, others need to be effected immediately. For instance, for new build, careful site planning and taking account of orientation must happen now, as would specifying a well-insulated building fabric and inward opening windows. However, solar shading could be provided later, as long as fixings are incorporated into the initial designs to make any future adaptations easy and feasible.

Whatever the future holds, we cannot afford to be complacent – especially as the measures above, and many more, can be easily incorporated into current procedures as part of good design practice. Given the required foresight and planning, we might be able to provide buildings which aid mitigation efforts – and if need be – support the future adaptation of our cities for years to come.

Whatever the future holds, we cannot afford to be complacent – especially as the measures above, and many more, can be easily incorporated into current procedures as part of good design practice. Given the required foresight and planning, we might be able to provide buildings which aid mitigation efforts – and if need be – support the future adaptation of our cities for years to come.